This week I begin an attempt to better understand, or at least to frame, the underlying issues between China and America beyond the headlines. From the Chinese perspective. Specifically, I want to (briefly in writing) walk a mile in another’s footsteps. It is a path without end, and this is but a beginning.

Introduction: Walking a Mile in China’s Shoes

Part I: China’s Perspective on America

One More Thought (Anna May Wong)

Introduction: Walking a Mile in China’s Shoes

Like many, I have questions about China and America. They are high level, dealing with everything that makes each country tick. They are ground level, dealing with waking up and going to sleep and managing daily life in between. The effort to reflect on these questions can make my head hurt.

China is becoming a superpower. America is a struggling superpower. Are these relative positions based on supreme confidence or latent inner doubts? A desire to be in control or not to be controlled? A combination of all? Optimism is a motivator. Dread is an anchor. Vice versa too. These are powerful forces in today’s strained and polarized world, a world in which ideology is strengthening and every argument or proposition generates a swift and ferocious counter-response. Stepping outside comfort zones in such an environment is a challenge.

For the next few Issues, I hope to stretch my comfort zone as I attempt to walk a mile (or should it be kilometer) in China’s shoes.

Part I: China’s Perspective on America

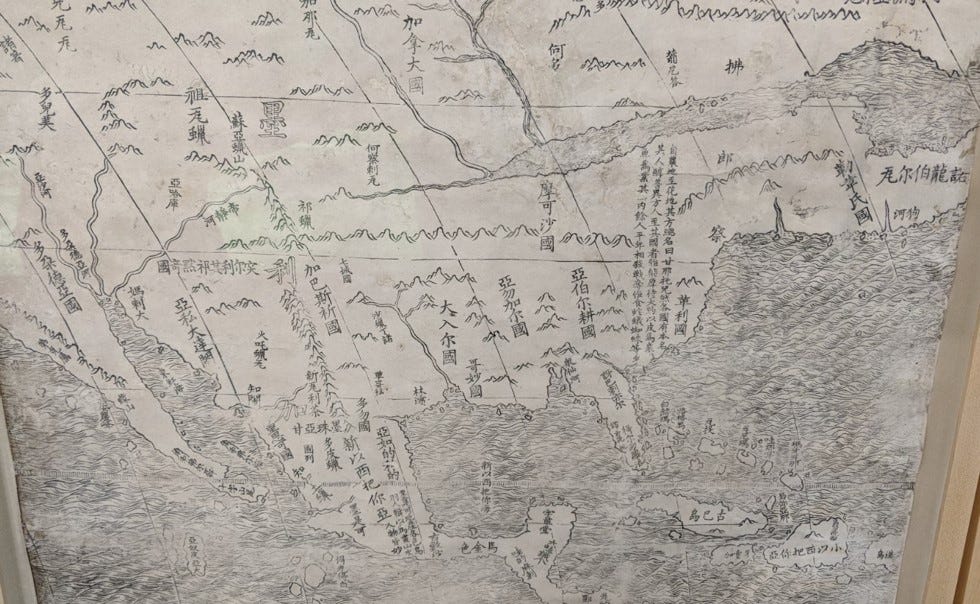

While it sounds cliché to say that the Chinese take a long view of history, the statement is not also wrong.1 The past is important in Chinese culture and society and is incorporated in subtle and express ways in the then presents. Indeed, such an approach took a beating during the Mao years when breaking with anything and everything old was the mantra, and it is being used today to overtly attempt to shape the present and future. No matter how the rationale has changed over time, history remains alive in China.

What do the Chinese see when looking across the Pacific at America? As David Moser has written, Americans may not be well versed on China, but the Chinese are well versed on America. They have been increasingly so since substantial numbers of Chinese visitors and migrants began traveling here during the nineteenth century.

The Chinese see in America a country with a complicated history, a sullied allure that still shines for many in China. The Chinese name for America, 美国, meiguo, means “beautiful country.” Yet it is a land both beautiful and bullying. It is a land of both promise and peril. This push and pull is part of the collective Chinese psyche. The beautiful and the promise predominated in the last two decades of the twentieth century; the bullying and peril are now ascendant. It is a roller coaster with a long pedigree.2

Nineteenth Century (First Half). I recently read the following Alexis de Tocqueville quote on a LinkedIn feed about Asia,

“If we reason from what passes in the world, we should almost say that the European is to the other races of mankind what man himself is to the lower animals: he makes them subservient to his use, and when he cannot subdue he destroys them.”

While this quote, which is from Chapter XVIII of de Tocqueville’s 1838 book On Democracy in America, was written about European settlers in America in relation to Native Americans and African slaves, the Chinese can easily pick out this Western intellectual thread woven throughout European and later American mindset and conduct in Asia from the beginning of maritime contact in the sixteenth century to outbreaks of the Opium Wars of 1839 and 1856 and beyond.

At the same time, mid-century America was the exotic, mysterious, and beckoning “Gold Mountain,”3 the land where adventurous (and desperate) Chinese men could escape the poverty, famines, and civil wars of China to reap fortune on the streets of California and provide for family back home. It did not work out well for most, but the dream was strong.

Nineteenth Century (Second Half). In the latter half of the nineteenth century, numerous treaties were signed between China and the United States. By their language, these were initially intended to open economic connections between the two countries and expressed desires of friendship and comity. They quickly evolved, however, into ever more restrictive regulations limiting, controlling, and then banning Chinese from entering America, having rights in America, and becoming part of America.

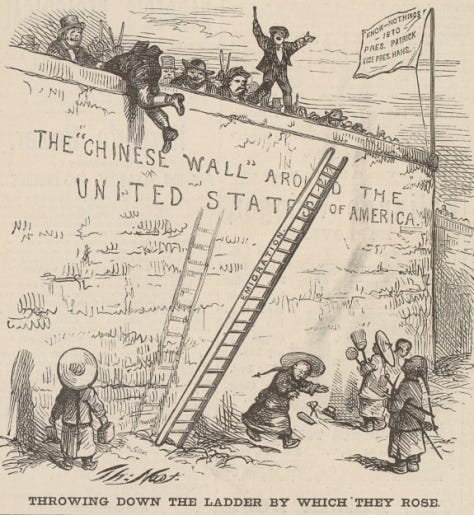

The Chinese were depicted in widespread American political cartoons4

“…to create fear and hatred of the Chinese…[, to] illustrate the cultural inferiority of the Chinese in order to justify white supremacy…[, to depict] interracial relations between the Chinese and other ethnic minorities, some of which functioned to create division among the various ethnic groups…[, and to predict and] describe what would happen if there were a Chinese takeover.”5

The Chinese Exclusion Act (which was initially adopted and then extended and expanded over many decades beginning in the early 1880’s) was not repealed until 1943. Not so coincidentally, it was only repealed when the U.S. and China were allies in World War II fighting against the Japanese. Prior to the Trump Administration, the Chinese were the only group to be specifically targeted for prohibition from entering the United States based on nationality.

This was also a period in which the Western powers carved up the China of the declining Qing Dynasty, each taking a piece as its own exclusive jurisdiction and control. The Americans were increasingly in on the action and played a significant role in putting down the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. The Imperialists were in charge of the Middle Kingdom.

Twentieth Century (middle). America was China’s enemy after the Communists took control of the country in 1949. Contacts were shut off. The countries went to war in Korea. Again not so coincidentally during our current clash with China, the largest grossing film in 2021 is a Chinese big budget ($200+ million) war movie about the Korean War. The Battle of Lake Changjin (known as the Chosin Reservoir in the West) has grossed close to $900 million dollars. The movie’s theme is a dramatic victory of Chinese troops over U.S. forces in a battle during the war. The Korean War in Chinese is known as the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea. The Korean War was followed in America by the McCarthy Era and persecution of suspected communists, whether Chinese or not.

Twentieth Century (Last Two Decades). The reestablishment of diplomatic relations with America and the reopening of China to the West after 1979 was a time of exuberant harmony between the two countries. When I first traveled to China in 1986, America and American society were pinnacles of cool and possibility and Americans were welcomed as acquaintances, friends, partners, and symbols.6

China was trying to recover after decades of disruption and were receptive to new economic models and opportunities. Education, employment, language study, travel, contact and communication were highly regarded. The Chinese not only began traveling abroad and visiting America, but hundreds of thousands of young Chinese eventually arrived on our shores to study.7

Relations at the person-to-person level remain warm and productive, though curtailed greatly by ongoing tensions and the closing of China’s borders to most visitors because of Covid-19. It is also true that throughout America’s earlier history of contact with China, even during the darkest times, there have always been numerous examples of Americans welcoming, promoting, and joining with the Chinese in America as Americans and working on both sides of the Pacific Ocean to overcome prejudices, biases, apathy, and vitriol.

Twenty-First Century (To Date). When China looks at America today, things are ugly. I have written before about a house divided v. a house united. We are a house divided. This enthralls China, scares China, encourages China, and provides cautionary tales to China, particularly the government.

In contrast to the infusion of history throughout Chinese language, cultural thinking, reference, and action, China sees an America that lives in the moment, seemingly without context or direction. They see a nation cleaved in two by opposing philosophies and goals and methods. They see intolerance, bitterness, violence, lack of public safety, and a credo of individualism close to the point of societal disintegration. They see a reactive, dysfunctional polity. They do not see stability.8

They see media, government, and wide swaths of the population that echo sentiments similar to those of the nineteenth century, even if not always as blatantly as two centuries ago. Each incident of anti-Chinese and anti-Asian prejudice and crime in America is trumpeted wildly in the Chinese media.

China sees an America that does not invest in itself, whether in infrastructure, education or research and development. They see the mal-effects of no-holds-barred capitalism and bloated consumerism as well as rampant income and wealth inequalities. They see a country that cannot rally around trying to fight a world-changing pandemic, whether by wearing masks, getting a vaccine shot or even agreeing that there is an issue of concern, all as more and more people get sick and die. We remain a symbol, but it is a vastly different one than existed in the 1980’s.

The Chinese see a country that attacks them for human rights violations, suppression of free speech and assembly and press, and threatening democracy and rule of law. Yet, the government believes that China’s version of governance is a socialist democracy that is equally valid (and working). And the Chinese are often confused (and then angered) by American attacks because they see that America routinely fails to promote and protect such freedoms and practices in its own country. They see hypocrisy and self-righteousness coupled with endemic racism and injustice. They see a nation that has a checkered history of foreign affairs enforcing its version and vision of a world order across the globe. They see a powerful nation, a nation whose military reaches deep into Asia and whose economy remains ahead in many aspects of technological and financial dominance.9

They see a country that fears China, scapegoats China, and wants to contain her rise and ensure continued American dominance.

In responding to this week’s announcement of a U.S. diplomatic boycott of the upcoming Olympic games in Beijing, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman stated

"Out of ideological bias and based on lies and rumors, the US is trying to disrupt the Beijing Winter Olympics. This will only expose its sinister intention and further erode its moral authority and credibility."

At the same time, hundreds of thousands of Chinese young people still study and work in America and more want to come. This is notwithstanding the suspicion and harassment of Chinese scholars in the U.S., particularly since 2017. Many Chinese are genuinely interested in America. Many Chinese support (or do not oppose) ideas and values that the U.S. ostensibly espouses. Many Chinese are proud of China and receptive to America and believe that the two do not have to be mutually exclusive.

The Chinese government faces a conundrum with America. We appear vulnerable yet remain a threat. Opening up to the outside world has resulted in China’s incredible growth and development, launching it back to world power status. At the same time, however, it also opened up China to negative influences that can threaten not only the population, but also the government. The delicate dance of the Chinese government is how to prevent or mitigate the latter without quashing the former. For this, the Chinese continue to study America.

One More Thought

I wrote here recently about early twentieth century, Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong as she will be profiled on a U.S. quarter next year. This story by Substack writer and self-proclaimed obsessive fan, Katie Gee Salisbury, “Long Live the Wong Dynasty,” provides a richer exploration of Anna May’s family, career, and life. She and her youngest brother, seventeen years apart in age, are described as “…both garrulous, fun-loving people with the same streak of iron-willed stubbornness that seemed to run through certain members of the Wong family.”

Follow Andrew Singer on Social Media: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter.

Photo of Ricci 1602 Map Section by author

LiLi Nacht - Day 35 of “What Does It Take To Know Freedom?” Performance Painting from https://supchina.com/2020/10/22/fifty-paintings-for-fifty-states-a-chinese-american-artist-reflects-on-freedom/. See also https://www.instagram.com/lili.nacht/?hl=en

Chinese Gold Miners (Illustration) - by Roy Daniel Graves 1889-1971), Wikimedia Commons

Throwing Down The Ladder By Which They Rose (Cartoon) - by Thomas Nast, 1870, https://thomasnastcartoons.com/2015/01/06

Coming Man: 19th Century American Perceptions of the Chinese, Philip P. Choy, Lorraine Dong, and Marlo K. Hom, Editors, University of Washington Press, 1994, Page 102

Coke Can (photograph) - by ernest-brillo-ryTknbJzLLQ-unsplash

Statue of Liberty (photograph) - by rehan-syed-spP5WTH7U8Q-unsplash

Portland, Oregon Protest (photograph) - by Jonathan House, cpj.org

Navy Vessel (photograph) - by stiven-sanchez-ngeJJFrTf14-unsplash