The ongoing global preoccupation with physical and digital border walls has me thinking about ancient walls in China. Not the Great Wall (a myth-shrouded favorite of mine), but rather at one time, more prosaic city walls. China used to have thousands. Now very few remain out of ruin, or at all.

The City Walls China Built

Bike Riding on an Ancient Chinese City Wall

One More Thought

The City Walls China Built

Since early in their recorded history, some four to five thousand years ago, the Chinese people employed fortified construction for their settlements, villages, towns, and cities.1 Advantageous topography (for defense, trade, and communication) has long been a consideration in where humans decide to live, and thus settlements were often near rivers, backed by mountains, and protected by other natural boundaries.

Primitive agricultural communities first developed along the Yangtze and Yellow River basins in China. The enclosures around settlements were initially simple perimeter ditches. To accompany basic ditches, there might be a low, mounded earth wall. Ditches begat moats, and the earth dug for the water barriers could be used to elevate the interior living area for protection from floodwaters that have always plagued both rivers.

Mounded earth walls gradually grew—wider, taller, sturdier, as engineering prowess advanced. Former earthen barriers, sometimes mixed with stone and rubble, gave way to the now familiar, fearsome rammed earth walls, often faced with bricks and stones. Foundations were constructed. Gates, some quite intricate with soaring watch towers, led from the outer wall surrounding a city to the inner wall protecting the elite, to the most interior of walls enclosing the palace.

Defensive capabilities became increasingly sophisticated as the residents had to repel developing offensive capabilities. Crossbows, exploding bombs, fire-launching catapults, battering rams, cannonballs. Walls could be over-topped, undermined, and blasted through. China’s history is a history of battles and wars.

City walls were expensive to build and maintain, required an enormous amount of manpower, and took a massive toll on the populace. City walls originally might have been round, elliptical or square. Eventually, in the Imperial era, most became recognizably square or rectangular (with some notable exceptions). The Chinese city walls we envision now are those expanded, constructed, and stylized during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Fortified settlements were never completely sealed off. They couldn’t be. The idea was to control access at limited points. Populations and resources both inside and outside the demarcation walls were also thus subject to control. In case of not infrequent attacks, city dwellers needed food, weapons, and supplies. If there was sufficient advance time, these could be relocated inside before sealing off the gates. This served a dual function. While it provided the city with the manpower and resources to withstand long assaults, it also removed potential resupply sources for the attackers who had marched far distances to do battle. When this did not work out as intended, starvation, depredation, and worse inside the walls was common.

Walled cities are the defining characteristic of China’s development. Osvald Siren (1879-1966), a Swedish art historian, had this to say in 19242:

“Walls, walls, and yet again, walls, form the framework of every Chinese city. They surround it, they divide it into lots and compounds, they mark more than any other structures the basic features of the Chinese communities. There is no real city in China without a surrounding wall, a condition which, indeed, is expressed by the fact that the Chinese use the same word cheng for a city and a city wall: for there is no such thing as a city without a wall. It would be just as inconceivable as a house without a roof. It matters little how large, important, and well ordered a settlement may be; if not properly defined and enclosed by walls, it is not a city in the traditional Chinese sense. There is hardly a village of any age or size in northern China which has not at least a mud wall, or remnants of a wall.”

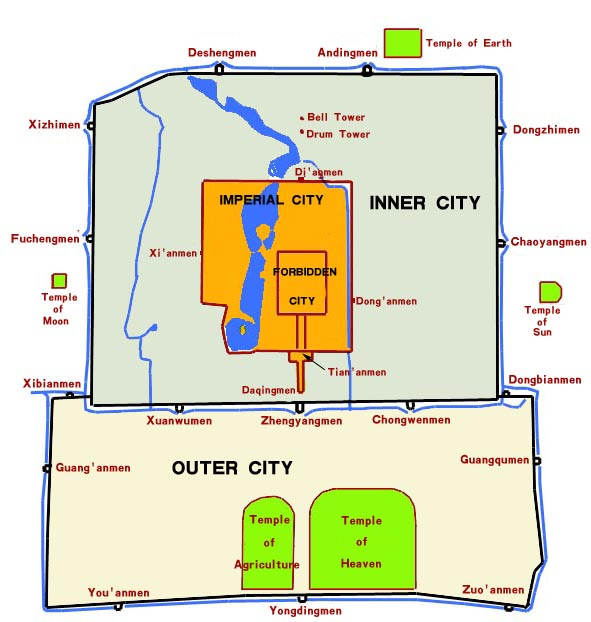

Beijing

Beijing’s city walls were intentionally dismantled in the mid twentieth century by the then-new Communist government. In their place (running mostly along the bed of the former moat around the perimeters of the Outer and Inner city walls) is now a ten-lane highway, the Second Ring Road. Memories of the former gates live on in the names of Beijing districts, streets, bridges, overpasses, and even subway stops, names such as Andingmen, Chaoyangmen, Dongzhimen, Fuchengmen, and Xizhimen.

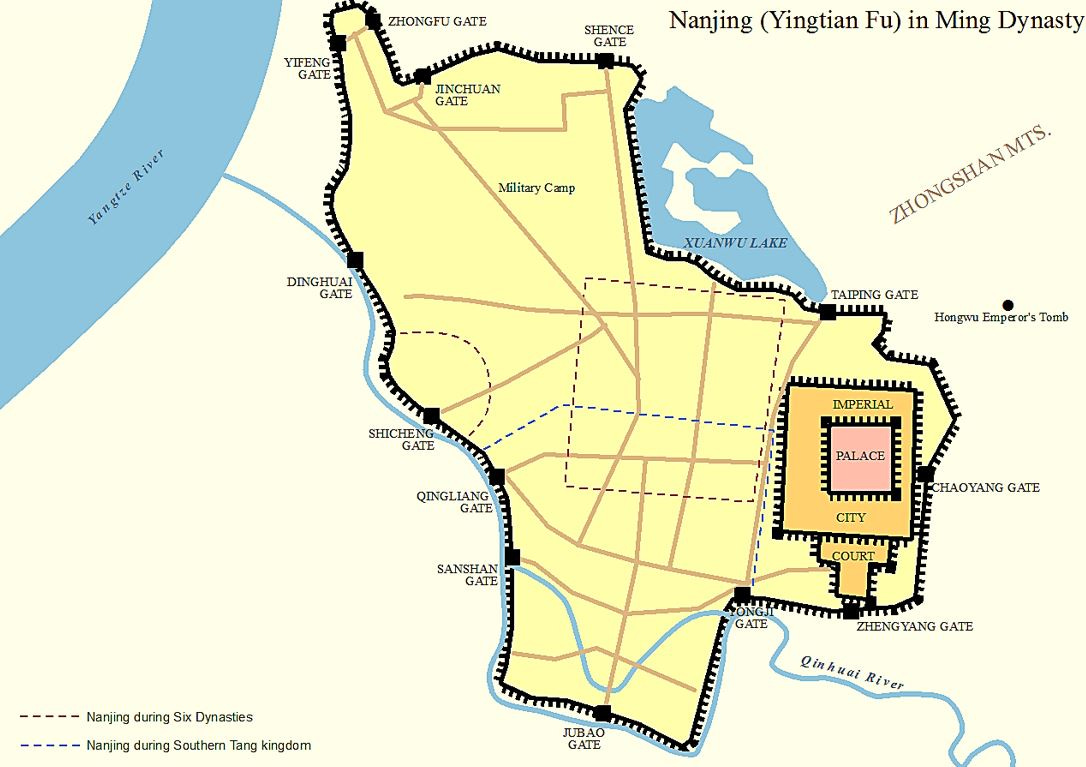

Nanjing

Much of the old city wall of Nanjing (the southern capital) remains. This is a prime example of a city wall that closely followed surrounding topography. Bordered by the Yangtze River to the north, the tributary Qinhuai River to the west and south, and with a large lake to the northeast, the ancient city wall of Nanjing is much more amoeba-like than its traditional Imperial counterparts.

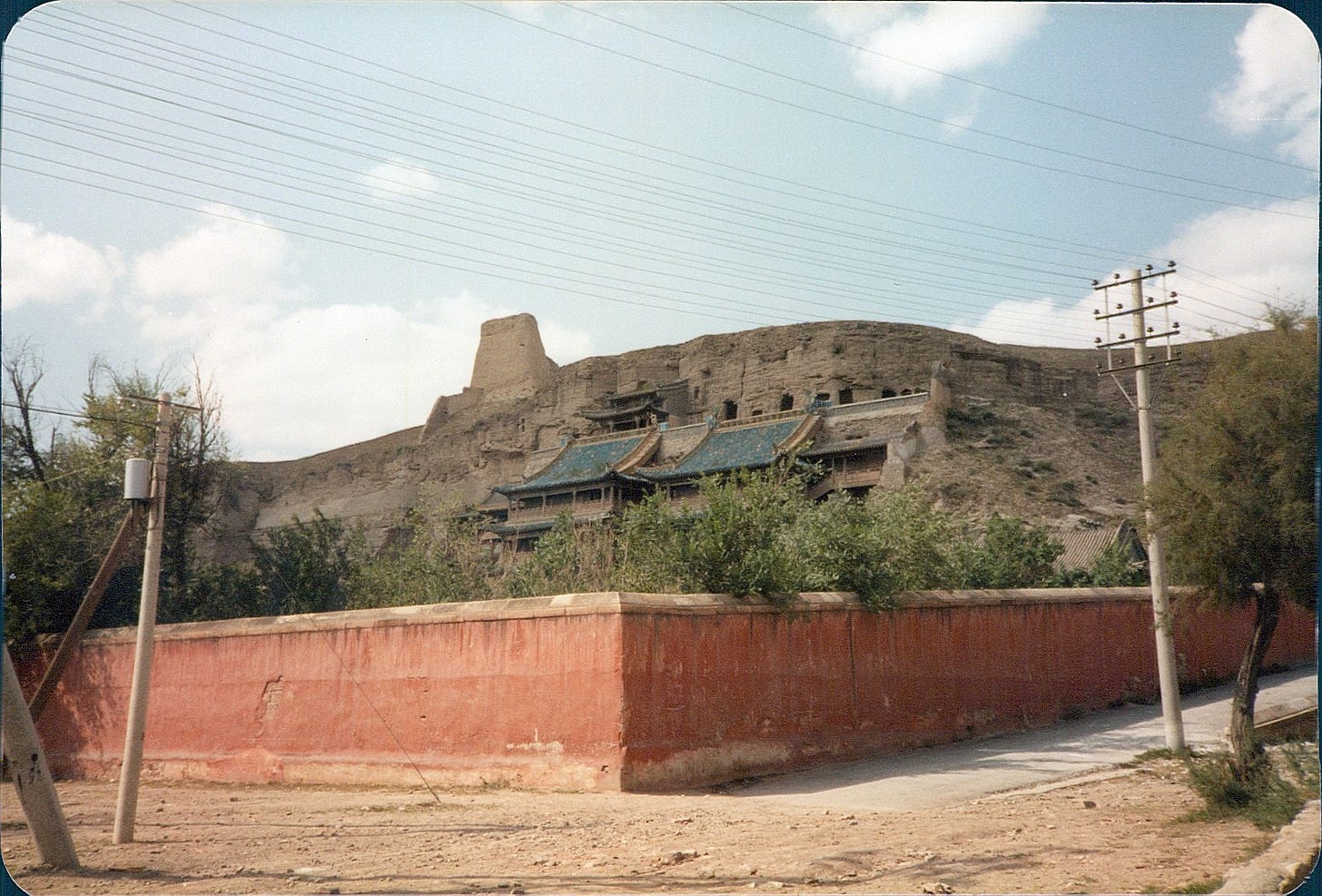

Datong

Datong, the northern Chinese city that has been home to three Imperial Dynasties (see Datong Dragon Screens), also had and has a city wall. However, the current wall is a twenty-first century reproduction in the Ming Dynasty style. The then-ruins of the original Ming Dynasty wall (itself much changed from its predecessors) looked dramatically different in 1986 when I visited.

From Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) city ruins near and in Zhengzhou and at the former Imperial capital at Kaifeng in Henan Province to the royal Xi’an (see next article) in Shaanxi Province, Pingyao in Shanxi Province, and others, there is much to explore.

Bike Riding on an Ancient Chinese City Wall

Ming Dynasty city walls were substantial affairs, and none more so than in Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi Province and jumping off point for the nearby Terracotta Warriors. Where cavalry and soldiers used to trod on the wide Xi’an city wall, bicycle-riding tourists now rule the roost.

The Ming Dynasty city wall was successor to previous walls in the area. The Qin Dynasty had a walled capital city nearby at Xianyang. The Western Han and Tang Dynasties had their respective capitals, both called Chang’an, on the site of present-day Xi’an.

The old city wall of the by then long-abandoned national capital of the Tang was restored when the early Ming Dynasty re-established a provincial capital at Xi’an. The Ming city wall, though smaller in scope than its expansive predecessor, was more substantial in bulk and more elaborately constructed.

Even at a reduced size, though, the perimeter of the current Xi’an city wall is almost 14 kilometers (8.5 miles) around. This is longer than it may seem when bicycle riding, particularly with a bumpy block travel surface and the need (ok, desire) to stop often and take pictures. In 2015, a fellow traveler and I rode all the way around the top of the Xi’an old city wall. Unfortunately, we had not let the others in the group know we were doing this, and they almost sent out scouts to look for the two missing middle-aged guys when we did not arrive back at the agreed-upon hour. We were winded and sweaty when we returned, but we did it.

When I next visited in 2017, they had blocked off one of the quadrants of the wall in the southeast corner, and we could only go about halfway before having to return by the same route. Still fun, but it lacked the same feeling of accomplishment.

One More Thought

Anna May Wong (1905-1961), a Hollywood actress in both the silent and sounds eras, will be among five notable American women featured on US Quarters beginning in 2022. Wong was the first Chinese-American film star and acted in more than sixty movies. “In a press statement, U.S. Mint Acting Director Alison Doone said, ‘These inspiring coin designs tell the stories of five extraordinary women whose contributions are indelibly etched in American culture.’”

Follow Andrew Singer on Social Media: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter.

Except as noted below, photographs are by the author:

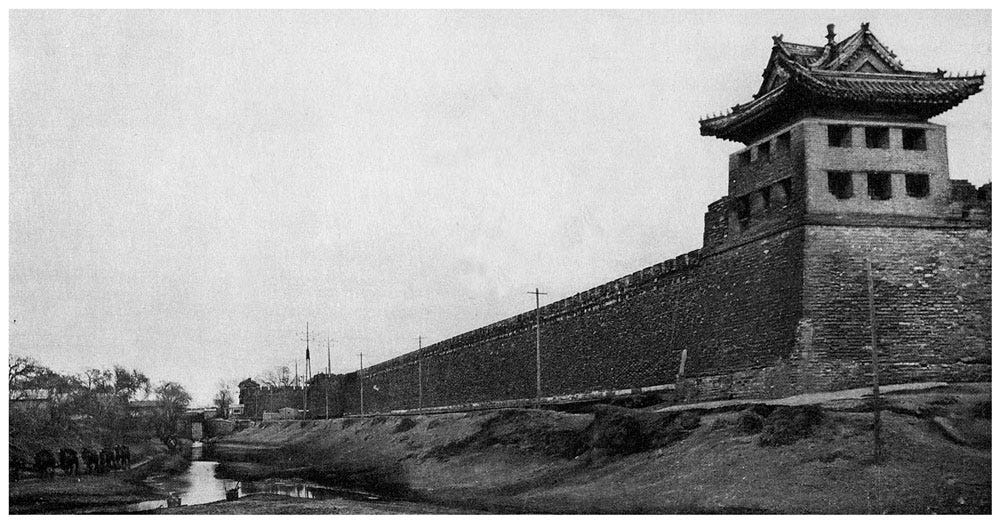

A. Peking city wall (northwest corner) - https://beijingofdreams.com/images/fixed/northwest_corner/peking.gates.085.a.jpg

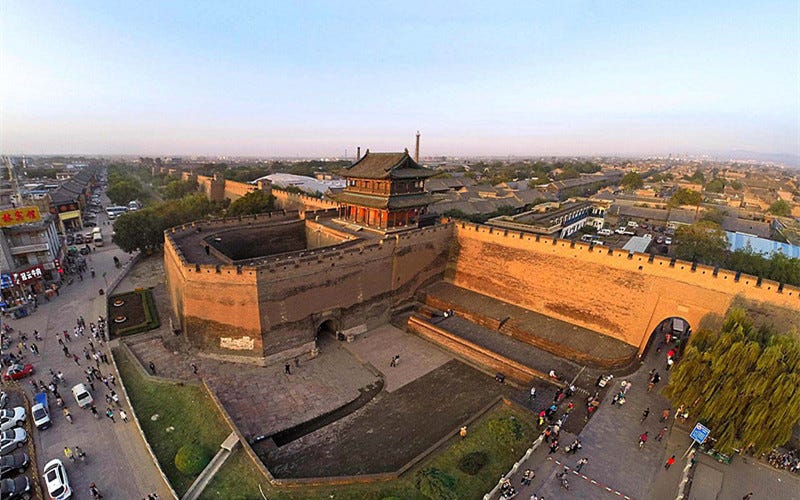

B. Pingyao city wall - https://www.chinadragontours.com/ancient-city-wall-of-pingyao.html

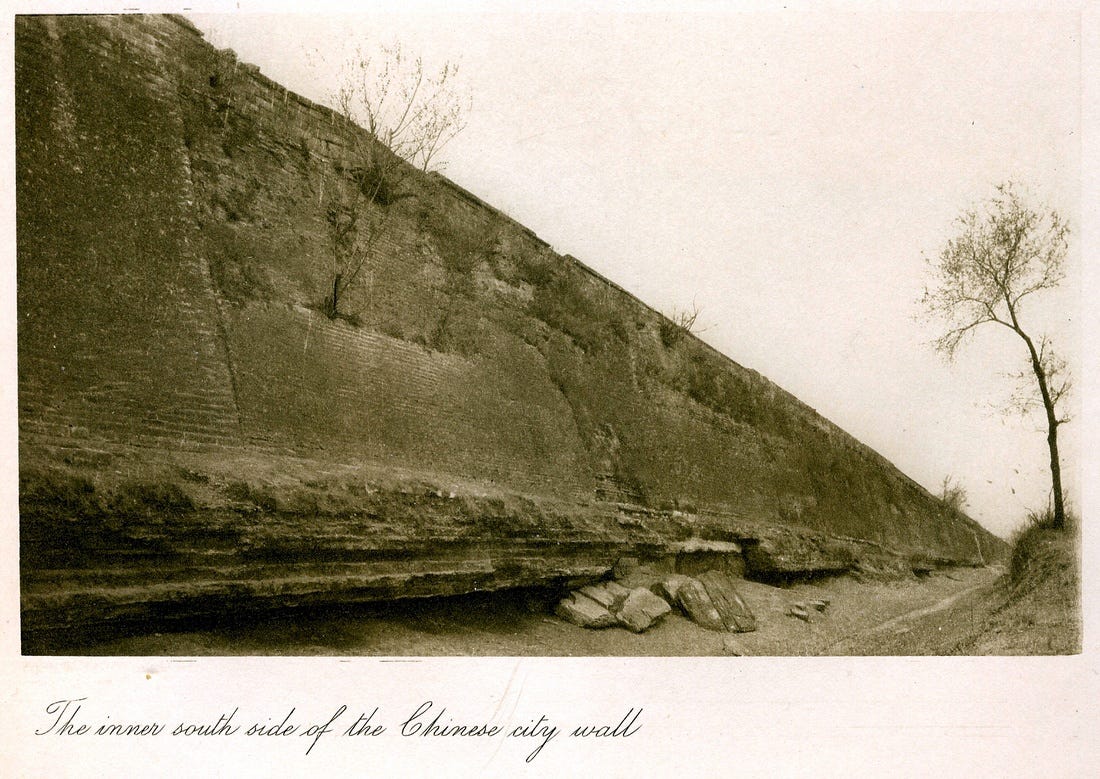

C. Peking city wall (inside south side) - https://photographyofchina.com/blog/osvald-siren

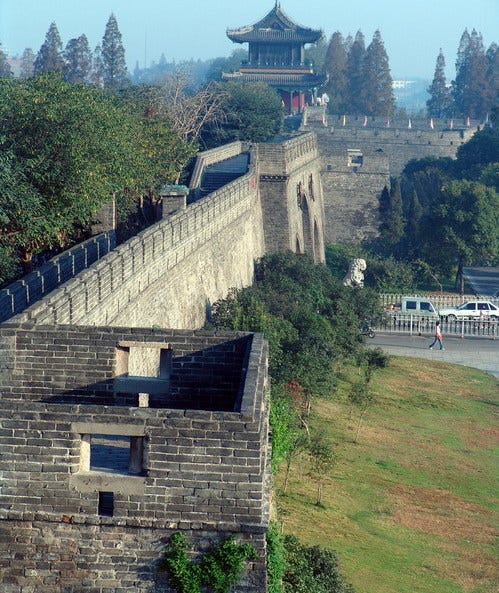

D. Jingzhou city wall - https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/m/hubei/travel/2011-11/22/content_14286914.htm

E. Beijing city wall map - By kallgan - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1408925

F. Nanjing city wall map - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nanjing_in_Ming_Dynasty.jpg

Stephen Turnbull, Chinese Walled Cities 221 BC – AD 1644, Osprey Publishing, 2009, Page 5, and Julia Lovell, The Great Wall: China Against the World 1000 BC – AD 2000, Grove Press, 2006, Page 25