This issue has spontaneously emerged with a literary theme, that of the great Spanish writer, Cervantes, and his most famous creation, Don Quixote, aka the Man of La Mancha, and their intersection with China and me. The China Resources section shares an essay from translator Howard Goldblatt on Chinese novel writing style. I hope you enjoy the old knight’s quests and new journey.

Don Quixote: From Spain to China and Back

“Chinese Don Quixote is translated into Spanish after 100 years.” This recent headline in The Guardian newspaper online caught my eye.1

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, known to most simply as Cervantes, was a Spanish author who wrote what was to become a masterpiece during the early seventeenth century. Don Quixote (El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha {“The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha”}{Part 1} and Segunda parte del ingenioso caballero don Quijote de la Mancha {“Second Part of the Ingenious Knight Don Quixote of La Mancha”}{Part 2}) is an adventure story.

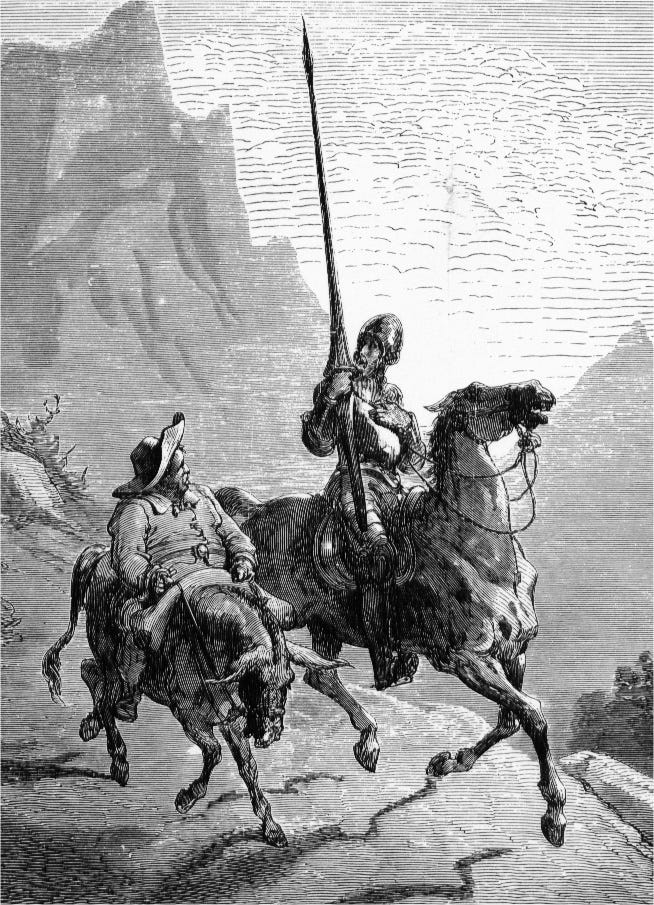

Don Quixote is an aging gentleman from La Mancha, Spain, who sets out to seek glory in the name of his (assumed) love. Accompanied by his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, they ride off on elegant steeds (a tired old horse and a donkey). He does battle with mighty forces (a windmill and a herd of sheep). There are enchantments, cruel jokes, and injuries galore as this good and honorable, yet misguided, soul is thwarted at every turn. But not until the very end, does the noble knight return home, defeated and ill, to die.

So what does this have to do with China?

Three hundred years after Cervantes, Lin Shu, a Chinese “man of letters,” translated more than 180 works of foreign fiction from several dozen authors and almost a dozen countries into Classical Chinese.2 He was a literary celebrity during the late Qing and early Republic Periods in China. Yet, he did not speak any foreign languages and instead relied on oral interpretations of the works to be translated by twenty, multilingual, Chinese assistants.

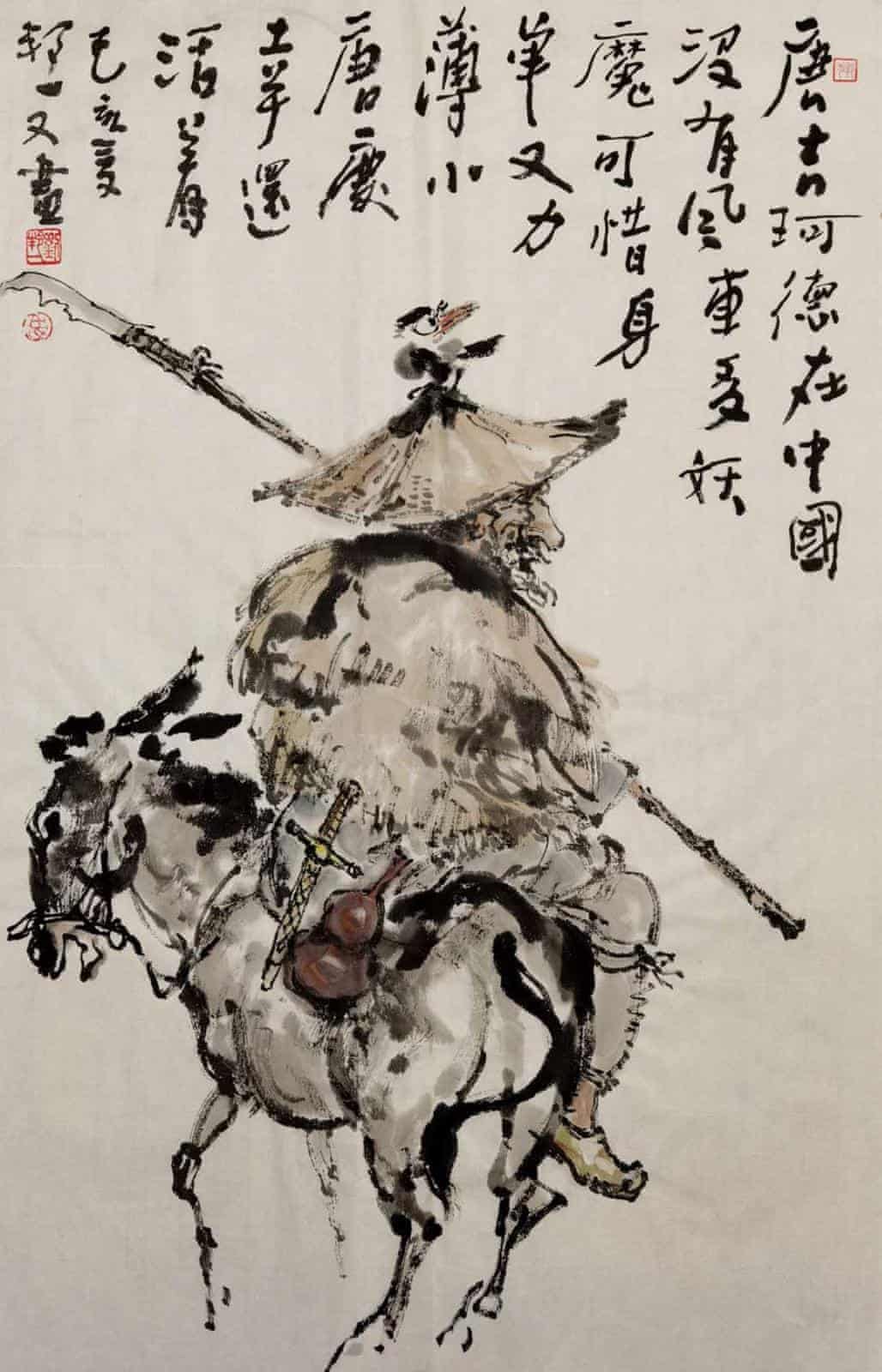

Lin translated a breadth of literature, from Dumas to Beecher Stowe and Aesop to Dickens, from Balzac to Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Hugo, and of course, Cervantes. In 1922, Lin translated the first part of Don Quixote with the name, The Story of the Enchanted Knight. As The Guardian writes, his Don Quixote, Sancho Panza, and Dulcinea are not quite the same as the Spanish originals. The hero is “less deluded and more learned.” Sancho is “more the disciple of a cultured master than squire to a mad knight.” And the heroine is not a peasant woman, but rather the “Jade Lady.”

The translations were often not faithful to the originals, and indeed were effectively translations of translations or interpretations, but they opened the world of foreign literature to China at a time of great change in the country. Commentaries on Lin’s work note that his translations say as much about China and her culture and history and aspirations as they do about those of the native lands of the foreign authors and novels themselves. Books have been written analyzing Lin Shu’s translations, his processes, and his life.

Now, almost a century after the publication of the Chinese Don Quixote and in honor of the 405th anniversary of Cervantes’ death, Lin Shu’s Chinese translation of the story has itself been produced in Spanish. Translated by Professor Alicia Relinque (University of Granada), in collaboration with the Instituto Cervantes in China, the Spanish version of The Story of the Enchanted Knight is accompanied in China by a re-publication of the original Chinese version from 1922. Lin Shu’s story is once again being told.3

The Man of La Mancha, Cervantes, and Me

My life has had a few memorable interactions with Cervantes and his literary creation.

I met Cervantes in China in the Fall of 1986, during my junior year abroad at Beijing University. The City of Madrid, Spain, donated a bronze statue of the famous author to Beijing after they became sister cities. The statue, which is a replica of the statue in the Plaza de la Villa in Madrid, was installed in an alcove of woods cut out just north of my dorm at Shao Yuan Lou several weeks after I arrived. The photograph above is Cervantes in Spring, 1987, when I took my visiting parents on a tour of campus. My mother and I are on the far-right side. I enjoyed the quiet, secluded nature of the statue.

When I next returned to campus in 2009, I made my way over to Cervantes. As can be seen in the photo below, he is no longer so secluded, but he remains steadfast on his perch. The Museum of Peking University History now sits to the north, and the Lotus Pond seems closer than I remembered. While this is my most recent encounter with Cervantes, my relationship with him, or more accurately, with Don Quixote himself, stretches much farther back.

My only date with a girl I liked back in my early teens (it took me forever to screw up the courage to ask her out) was to a performance of the Man of La Mancha Broadway musical, a 1965 adaptation of Don Quixote.

The words to the most famous song from the musical, “The Impossible Dream,” spoke to me then as now.

"The Impossible Dream” (music by Mitch Leigh with lyrics by Joe Darion):

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

To right the unrightable wrong

To love pure and chaste from afar

To try when your arms are too weary

To reach the unreachable star

This is my quest, to follow that star

No matter how hopeless, no matter how far

To fight for the right, without question or pause

To be willing to march into Hell for a heavenly cause

And I know if I'll only be true

To this glorious quest

That my heart will lie peaceful and calm

When I'm laid to my rest

And the world will be better for this

That one man scorned and covered with scars

Still strove with his last ounce of courage

To reach the unreachable star!”

China Resources

This 2008 essay by translator Howard Goldblatt on the differences between the openings and styles of Western and Chinese novels has recently popped up on my Facebook feed, posted by Asian authors who live and write in both cultures.

The Western novel tradition is to seek the provocative opening hook, the initial sentence or paragraph that grabs the reader and doesn’t let go. Chinese novels, on the other hand, have a more “traditional-bound beginning,” grounded in shared culture, history, and location, that “…tend often to open with a geographical setting, sometimes in lyrical prose and at other times in a matter-of-fact style,….”

As Mr. Goldblatt notes, this is not to say that there not exceptions to these trends in different cultures, nor that either style is less or more worthy than the other. The love of reading is my takeaway from this essay, with a better appreciation of how different cultures approach their writing.

Follow Andrew Singer on Social Media: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter.

Photograph: Gustave Doré: Don Quijote de La Mancha and Sancho Panza, 1863

Photograph: De Lin Shu - Lin Shu, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8005710

Photograph: Liu Bangyi