“Seeing” Chinese Art - Li Keran and Me (Part I)

March is mid-spring on China’s lunar calendar. Winter’s grip has loosened, insects awaken, the vernal equinox arrives. It is a time of renewal, a time to entertain new possibilities. In this spirit, today I begin considering the vision of an artist-scholar friend for a more nuanced, transcultural appreciation of Chinese art aesthetics, and maybe a new way of thinking about the world as well.

A Li Keran landscape painting hangs in my stairwell at home. I have a dream that this rice paper scroll might be the real deal by the famous artist. I email photographs of my painting to Hugh Moss, a prolific collector, researcher and writer, and an accomplished Chinese ink-brush painter and calligrapher.

“Hi Hugh. Is this real?”

His initial response from Hong Kong:

“the Li Keran you sent pics of seems strange, so I'm checking it out,….”

A wispy path winds steeply upward from a shaded, pine tree forest into the rolling, rocky waves of a towering mountain in the shape of a stoic elephant elder. Three travelers, one with a red shirt, rest on their ascent, gazing up high at the natural wonder looming above them.

An inscription with a red seal stamp floats in the clouds at the top. It reads “1980, Yuan Xiaojie (the beginning of the Lantern Festival), Made by Li Keran.” The written description that came with the painting (I bought it years ago on eBay) calls it “a nice Chinese antique watercolor painting.”

Hugh and I begin talking about his transcultural vision of art. He views art as overall process, as something greater than the sum of its component parts. In his book, Art Reboot, Hugh contrasts the traditional, Western intellectual theory of art as object with the many realities and consciousness-plumbing depths of traditional Chinese art.

In transculturalism, art is enlightenment that breaks barriers, expands boundaries, and achieves a new state of being. The piece of art is not just seen, but rather, the artist and the audience dance in a symbiotic relationship that can stretch minutes to millennia.

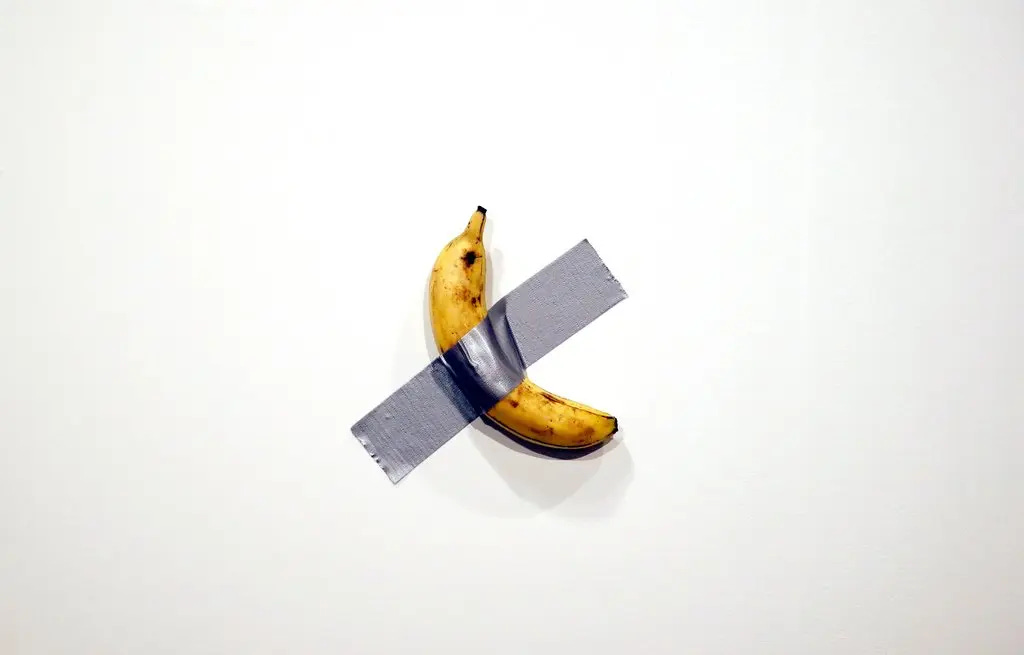

(photo by Rhona Wise.EPA, www.newyorktimescom)

To Hugh, the modernism that developed in Western art in the early twentieth century was us finally beginning to catch up to what the Chinese had been doing for centuries.

Duchamp’s 1917 urinal shocked as it interacted with the viewer; The stimulation of viewing, eating or possibly throwing away Cattelan’s banana is experience. The banana artist himself has said that "…he conceived of his work [in 2019] as a satirical jab at market speculation, asking the question, “On what basis does an object acquire value in the art system?”

The key to understanding Chinese thought, and art,” Hugh writes, “is to recognize that the ultimate goal of the culture philosophically and of art are identical: both aim directly and efficiently at the Absolute, the Dao.”

This is all a little above me, truth-be-told. I gravitate to a more straightforward art experience rooted apparently in an intellectual appreciation approach. I observe the object, be it painting, stone or bronze. I read the label on the wall. I look at the object again trying to make a mental memory. And then I move on.

Hugh would say I am missing the context for the rice paper. I am ignoring the involvement of the artist, his culture, earlier audiences, future audiences, and myself in the process of the painting becoming a painting, living, and evolving over time. As such, I fail to feel (to “see”) the Dao, the Way, flowing behind, within, and beyond the creation formed by the ink-brush strokes. I do not understand.

I expect that Hugh would agree at some level with Roger Fry, an early twentieth century, American art critic. Fry, a proponent of modern, post-impressionist art, challenged the prevalent formalist and doctrinaire Western vision of art:

“[Fry] saw the process of testing, revising, disproving and reconstructing as the norm, precisely because he expected to constantly encounter new forms of art that would inevitably be intellectually disruptive….[He sought to describe every work] as a unified whole, rather than as a set of categories or ‘boxes’ to be checked off.”1

Bananas, toilets, and almost anything now can be (no, are) art.

Vehicles for expression and self-cultivation of both artist and audience.

Experience. Perhaps, if fortunate, Transcendental.

This brings me full circle to my Li Keran landscape. Is it real? Is it fake? Does it matter? And the all-important, why? This is what Hugh has me now thinking. Part II will consider answers to these questions.

Follow Andrew Singer on Linkedin, Instagram, and Facebook.

Neil R. Rudenstine, The House of Barnes: The Man, the Collection, the Controversy, The American Philosophical Society Press, 2012, Pages 86, and 89.

Wonderful and thought provoking 'art'icle Andrew! 🏆

Andrew: I appreciate your very personal, self—effacing approach to Art appreciation, refreshing to say the least. . .