My Chinese professor once told me that if I did not expect anything (as I set off on my first trip to China), I would be pleasantly surprised. While I am not always successful in this (then or now), the unexpected often delights. This happened recently on a trip to California when I came upon a collection of exquisite, wooden Chinese panels in the home of new friends. These panels are alive not only with images of China, but also with their own, unique story. This issue looks at the Lum Panels.

The Lum Panels

The carved black and gilt panels immediately captured my attention. There are two sets of five, individually-framed wooden pieces mounted on offset, parallel walls as if they were doors. But doors into what and what were they doing hanging in a private residence in the Bay Area of California? I could not take my eyes off them. I had to learn more.

In their most immediate previous life, the panels were in fact parts of custom doors. The doors were among other decorations created for an antique shop in Hong Kong. The panels in front of me made up the doors that separated the retail gallery from the private office in the back of the shop. This was Ada Lum Ltd in The Mandarin Hotel.

Ada Lum (d. 1988) was a member of the social and economic scene of Shanghai in the early-to-mid twentieth century. According to a ship manifest, this Australian-Chinese woman emigrated there with family members on the S.S. Taiping, which departed an Australian port on December 13, 1927. Her brother, Gordon, was a famous tennis champion.

Ada herself became renown for designing and creating handmade, authentic Chinese dolls. This hobby became a business that is still a collectible today. She also wrote for literary magazines and was herself profiled in the press. Anna May Wong, the Chinese-American Hollywood star, writes of spending a “delightful shopping trip with Ada Lum,…” one afternoon during her 1936 visit to Shanghai.1

In 1949, the extended family fled Shanghai to Hong Kong. Ada opened a shop and then relocated Ada Lum Ltd to the newly-opened Mandarin Hotel in 1964. The Mandarin had replaced the late 19th Century, Neoclassical Colonial Queens Building in 1963. The 27-story hotel was not only uber-luxe for the time, but for three years it was the tallest building on Hong Kong Island. It was the first hotel in Hong Kong with direct dial telephones as well as baths in every guestroom.

Because she was the first to take space in the hotel’s commercial mezzanine, Ada had her pick of retail spots. She chose the prime one at the top of the stairs. Ada was the go-to person for Chinese antiques dealers because she “recognizes and respects quality.”2 The store remained open at The Mandarin until 1990, when family members relocated again to California. They operated the shop in the Bay Area for a couple of years before closing for good.

The wooden panels are from Chinese temples. During the early 1960’s in Fujian Province, a time of disruption, poverty, and hardship in China, there was an organized syndicate whose agents procured objects (from sources legitimate and not). The objects were stored in China before being transferred to Macao factories with export permits that labeled them wooden parts for restoration. Eventually, they were sent to Lascar Row in Hong Kong for resale.

Ada visited Lascar Row in the company of her young nephew acting as translator. A relative who was an apprentice woodworker from Guangzhou skilled in the lacquer technique advised her on what to look for. Ada viewed more than 200 panels and selected several for the doors and screens she envisioned for her new hotel shop. The panels are dated to the early 1900’s Republican Period. Carpenters pieced them together and installed them in the store.

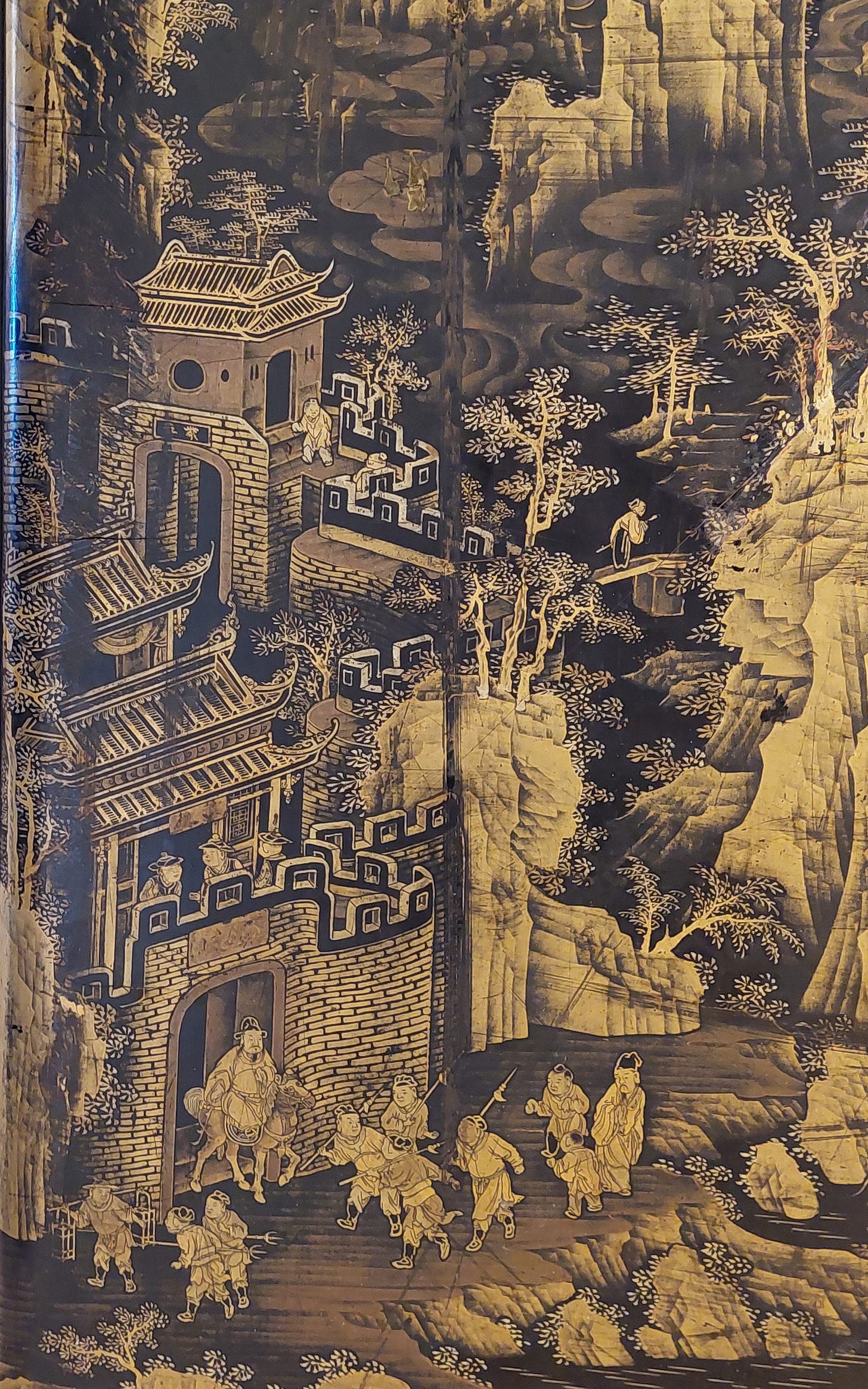

One of the large panels showcases a festival in progress. The city is well appointed with elaborate buildings and pavilions topped by ornate roofs. People crowd the boisterous scene. Inside. Outside. Engaging in conversation, observing, all with their roles to play. There are the serious and the demure, the curious and the free spirits, the happy and the discomfited. Such an expressive mix.

Officials on prancing horses parade through the streets being led by gongs and accompanied by attendants. There are soldiers. A couple looks down from a tower balcony. Elders receive guests. Musicians’ melodies liven the day. There are assorted amusements to entertain young and old. A mother holds her baby up to look out a window.

Excited children move along with families. One child holding a bent ruyi tugs on his mother’s robes.

A large bird peers down from the top of a doorway, while a boy appears to be trying to pull a strange horned animal through the raised doorsill from a garden.

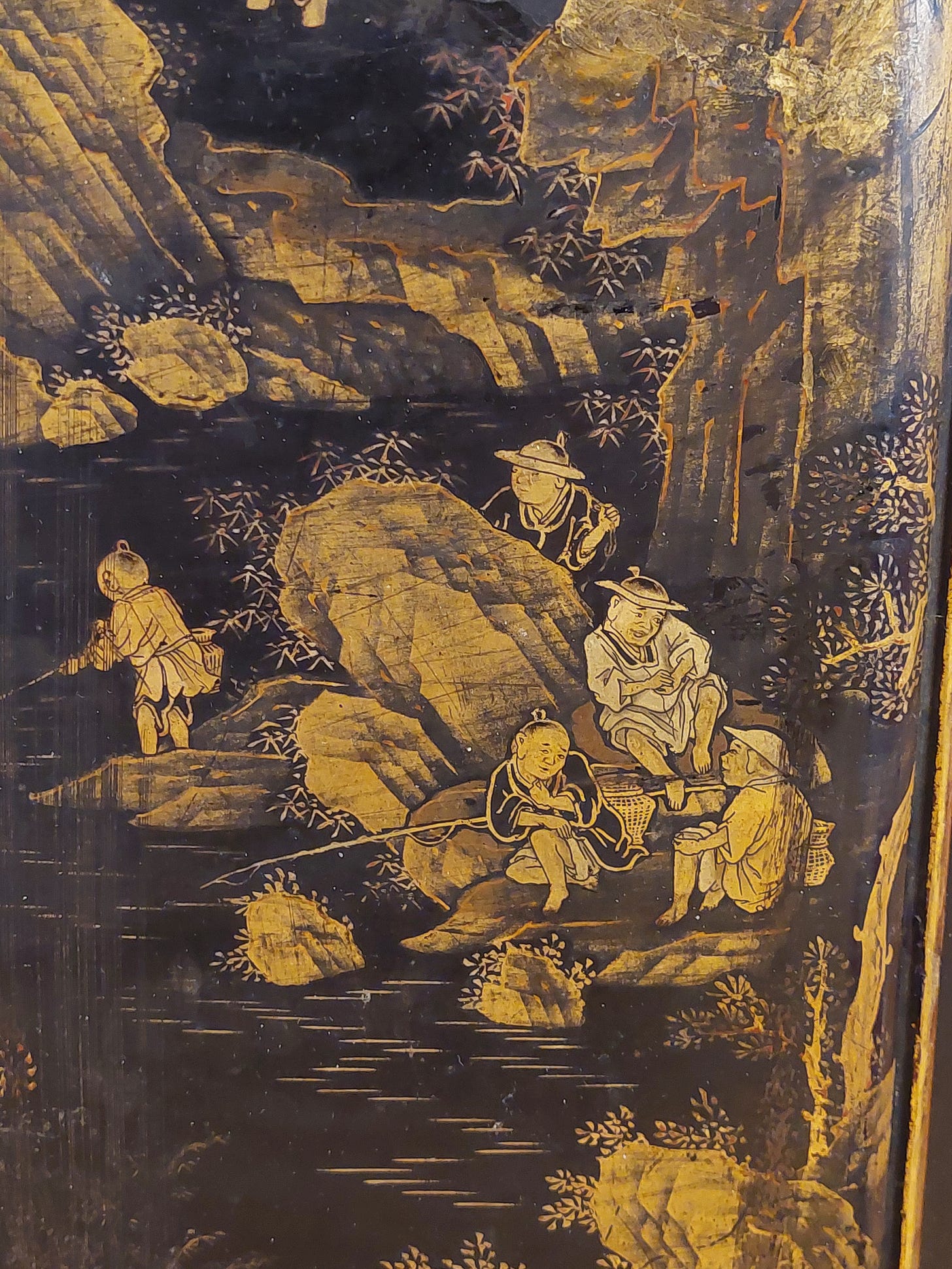

The other large panel showcases scenes outside the city walls. A poem on this panel is dated to the twelfth year of the Guangxu reign (1886) and is a poetic inscription composed by King Wen of the Zhou Dynasty (1152-1056 BCE). It discusses the King taking a break during a hunting expedition and seeing a group of fishermen resting nearby. The poem comments that the fishermen have no concept of the extensive scope of the universe nor that time is constantly passing them by while their hair turns white.

These pieces of China’s history were meant to be in the Lum Family, and they remain so in this twenty-first century. The walls on which they now hang with distinction belong to Ada Lum’s nephew (the young man who accompanied her to Lascar Row long ago) and his wife. They themselves are renown collectors of Chinese snuff bottles.

Follow Andrew Singer on Instagram, Facebook, and Linkedin.

Sunday Oregonian, Portland, June 21, 1936, cited in http://asiawee.blogspot.com/

Peggy Durdin, “Good Coffee & Good Jade,” The Mandarin Hong Kong Magazine, 1974

Fascinating panels, and the poem you reference sounds timeless

Thanks Andrew, lovely and insightful as I've come to expect from you. Regards Richard