Find me a store selling Asian antiques, and I am all in. Mention general antiquing, and my eyes tend to glaze over. Thus was I surprised during three, recent, unplanned antique store visits across America to come away with three treasures, two of which relate to Asia. In this Issue:

Antiquing Treasures – Chinese Buddhist Triptych

Antiquing Treasures – 1831 Map of the Indian Ocean and Asia

One More Thought

Antiquing Treasures – Chinese Buddhist Triptych

Brimfield, a small town in Central Massachusetts, is famous for annual, multi-day antiques fair extravaganzas. In the middle of it all is the Brimfield Antiques Center. We found our way there one morning before attending an evening wedding in the area.

As it happens, a New York Asian antiques dealer sells here, and this Buddhist Triptych caught our eye. It is just so peaceful and perfect.

Triptychs such as this are small, portable travel shrines that close to securely protect and preserve the sacred images within. They are versatile and can be carried, worn around the neck or hung from a belt. Devout followers of Buddhism, pilgrims, and monks used them to worship, meditate, and even teach, wherever they were in their journeys. That mobility was important is not surprising in a religion that began in India and migrated far and wide across the ancient land and maritime trade routes throughout the landscape of Asia.

According to the dealer, this wooden (rosewood? sandalwood?) Triptych likely dates from the early 1970’s. The shrine is relatively straightforward and simple with only three images. Often, such shrines are much more elaborate in number and scope of images, actions, teachings, stories, and more, as in these examples from The Walters Art Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

My research into the identities of the three images has in part led me down a rabbit hole. I have a best interpretation which I will discuss below, but it is not ironclad. Some items that are frequently associated with a particular image are missing or something else is added or hand positions are reversed. Some Buddhas and Bodhisattvas were considered and ultimately rejected. I believe that these images represent Amitabha (center), Guanyin (right), and Mahasthamaprata (left), the Three Sages of the West in the Pure Land tradition of Mahayana Buddhism.

Amitabha, the Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Life. I originally thought it was Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, which is understandable since the two represent two of the three bodies (forms) of the Buddha. With beaded hair and eyes half closed deep in thought, the Buddha sits with legs crossed on a lotus base. His hands are in the dhyana mudra meditation position. This position, in which the right fingers rest on top of the left fingers and the thumbs touch closing an open circle, unites the mind, body, and spirit and helps focus concentration.

Meditating worship with Amitabha, the follower considers the Four Noble Truths which are the essence of Buddhism – Life is suffering, suffering is caused by desire, letting go of desire is the way to end suffering, and following the Eight-Fold Path allows one to give up desire and end suffering. In the phraseology of Professor Rupert Gethin, these Truths are the disease, the cause, the cure, and the medicine.1 The Eight-Fold Path, the medicine, consists of Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Guanyin, the Bodhisattva who is the Chinese Goddess of Compassion. Guanyin started out in India as the male Avalokiteshvara. She also sits with legs folded high on a lotus throne, her eyes cast down to take in all people. Her right palm is in the abhaya approachability mudra position. The palm up and facing out, fingers stretching toward heaven, indicates the act of teaching and reassurance. In her left hand rests a slender bottle holding the pure water of life. This bottle is one of the eight Buddhist symbols of good fortune. Guanyin hears the cries of the world and represents mercy and compassion and acceptance.

Mahasthamaprata, the Boddhisattva whose name means “arrival of the great strength.” Dashizhi, in the Chinese, is a powerful Boddhisattva representing the power of wisdom. In this Triptych, Dashizhi sits with legs folded on a lotus throne, eyes also looking down. He holds either an alms bowl or a healing jar in his lap with his right hand, the left palm up and out in the abhaya mudra position. This identification turned out to be the most challenging because normally a small bottle or vase is associated with Dashizhi. In this trinity of Sages, it is said that Guanyin enacts Amitabha’s compassion and Dasshizhi brings to humanity the power of Amitabha’s wisdom.

This Triptych brings to mind the words of Kurt Behrendt, an associate curator at The Met, who has written that “...a correct sculpture is inherently pure and resonates with the power of enlightenment."2

Antiquing Treasures – 1831 Map of the Indian Ocean and Asia

An hour plus west of Seattle, Washington, beyond Bainbridge Island, sits a Viking town, Poulsbo. With free time while visiting the area, we discovered a quiet antique store on Viking Avenue. There was virtually nothing from Asia in this store.

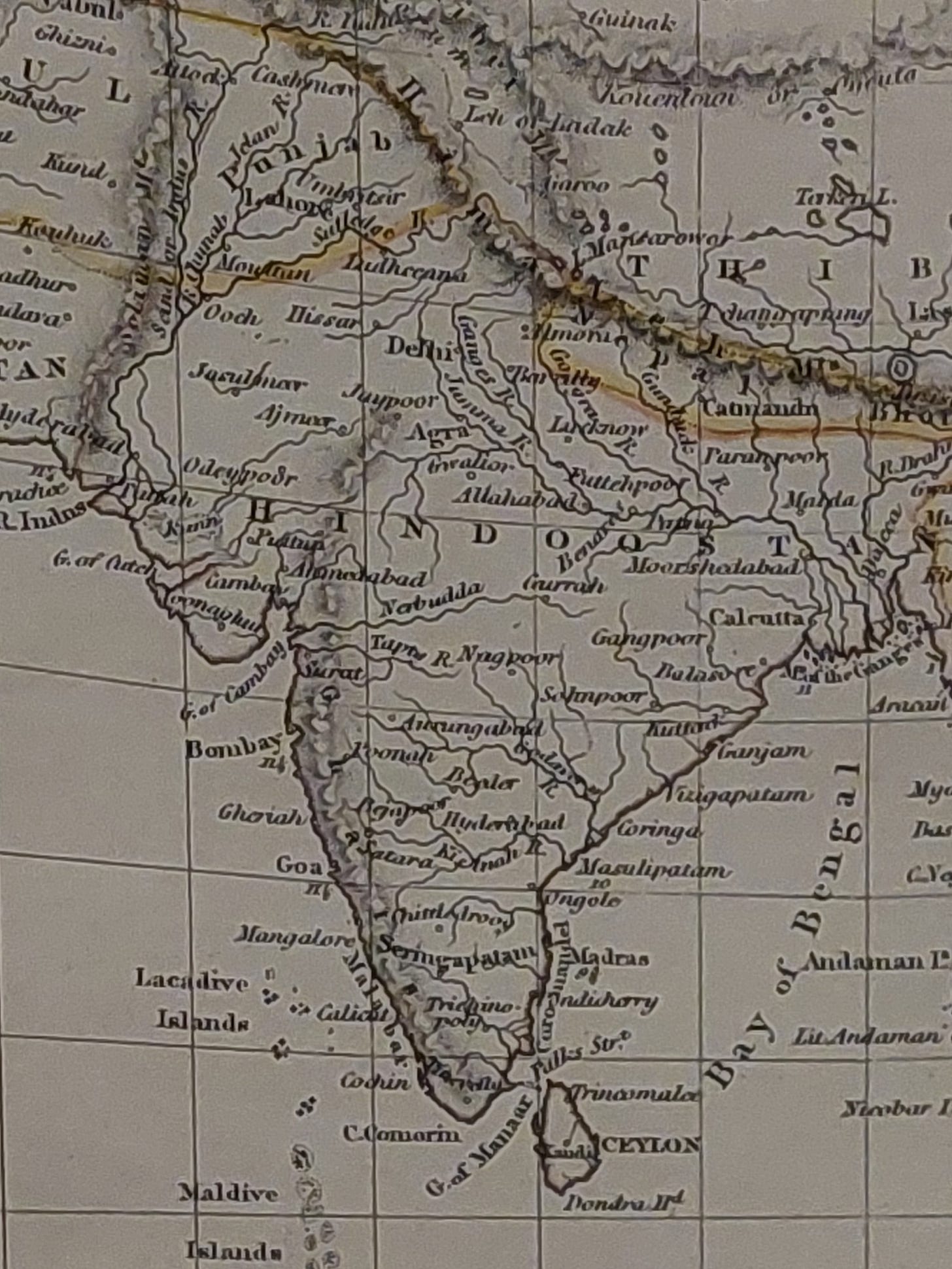

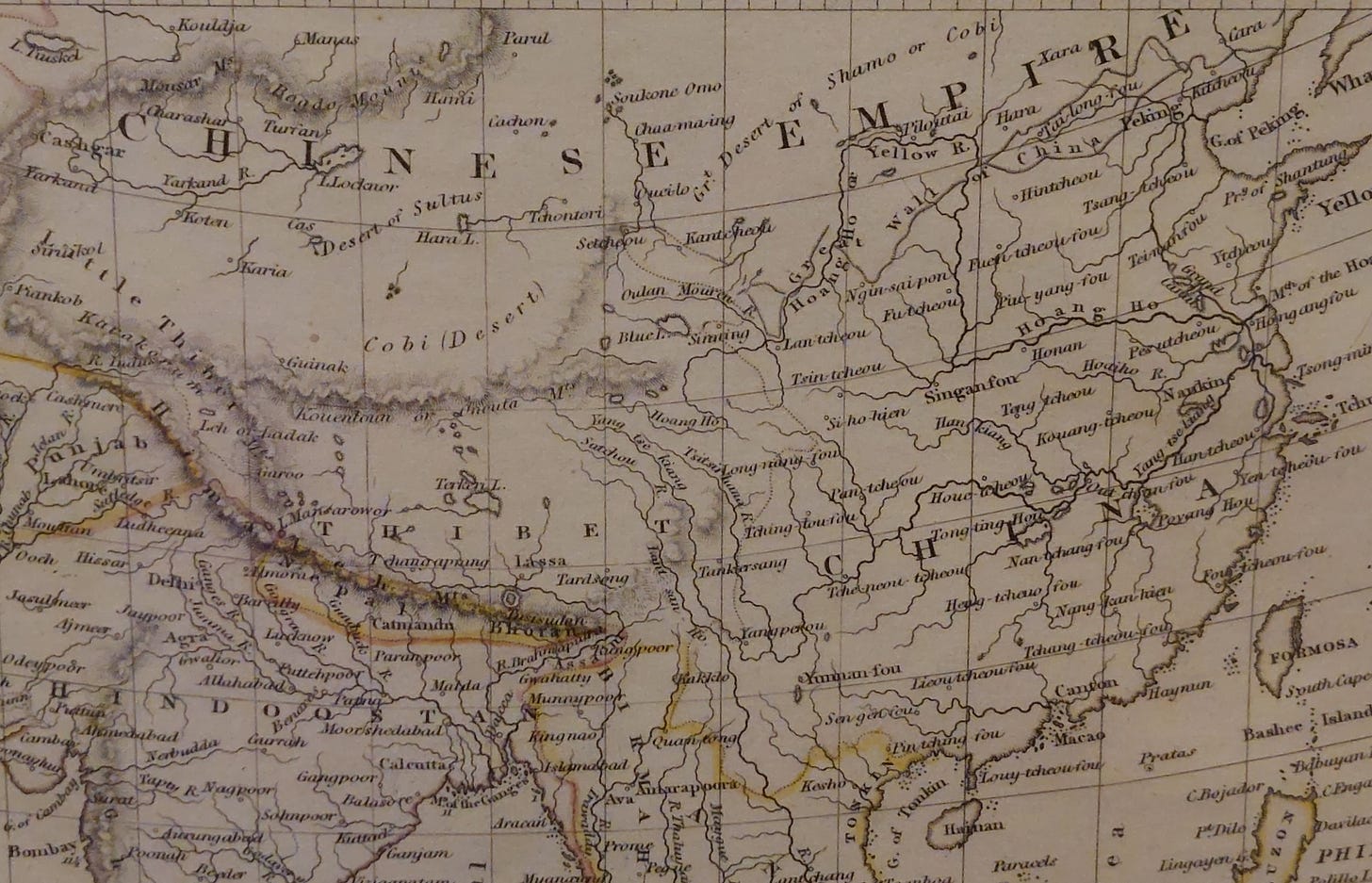

I almost missed this map, hung on an inner partition and overshadowed by surrounding items. Maybe it is that I like maps. Maybe even more that I have been researching maps of the ancient trade routes between Europe and Asia. Serendipity? How else to account that virtually the only Asian item in this store was this June 1831 Map of the Indian Ocean and Asia engraved by J. & C. Walker in London?

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge? Sounds like a sequel to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Turns out the Society was real. It was created in 1826 and disbanded in 1848. Its mission was to publish useful information in the arts, sciences, and of the world for the English working and middle classes, to spread information to other than the traditional educated classes. Promoting “self-education” and “egalitarian sharing” are two phrases I came across in looking up the SDUK.

The Society published treatises, magazines, and reference books under the headings of Library of Useful Knowledge, Library of Entertaining Knowledge, The Penny Magazine, and The Penny Cyclopedia. And they ran a Map Series. This was the crown jewel in the Society’s inventory. The map I discovered is of the Indian Ocean region and shows the area of the ancient maritime trade routes from northeast Africa and the Middle East to South and Southeast Asia and China.

The map series was a big production that ultimately led to the Society’s downfall. It turns out that producing beautiful maps with exacting detail and up-to-date information is expensive and cumbersome. A note at the bottom of my map states that “The figures along the coast show the time of High Water at the full & change of the Moon.” This was compounded by the fact that the head of the Map Series was apparently a perfectionist surveyor and cartographer. The maps--gorgeous, informative, and accurate, were thus issued too infrequently and at too prohibitive costs for the intended audiences.

The Society produced 200 separately issued maps initially published by Baldwin and Cradock and sold by subscription between 1829 and 1844. These maps were subsequently combined into a giant world atlas. The world maps, as well as detailed city plans, survive to the present as being “among the most impressive examples of mid-19th century English mass market cartographic publishing.”3

The combined atlas was issued in two volumes and contains no text, only maps. There are a total of 330 maps, including the continents, the countries of the world, and fifty detailed city maps. There are world maps, continent maps, regional maps, and country maps. Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, North America, the Caribbean, Central America, South America, and the Pacific Ocean, including the smaller islands as well as Australia and New Zealand, are all there in detail. The scope of the SDUK Atlas was all encompassing for the time.

Might my map be an SDUK original, a monetarily valuable piece of history? It sure looks old. I wish. The realist in me counters that since I paid $4.50 for it, frame and all, it is a copy. But I am good with that.

For those who want more information on the SDUK, Joe McAlhany has written an in-depth article at oldworldauctions.com.

One More Thought

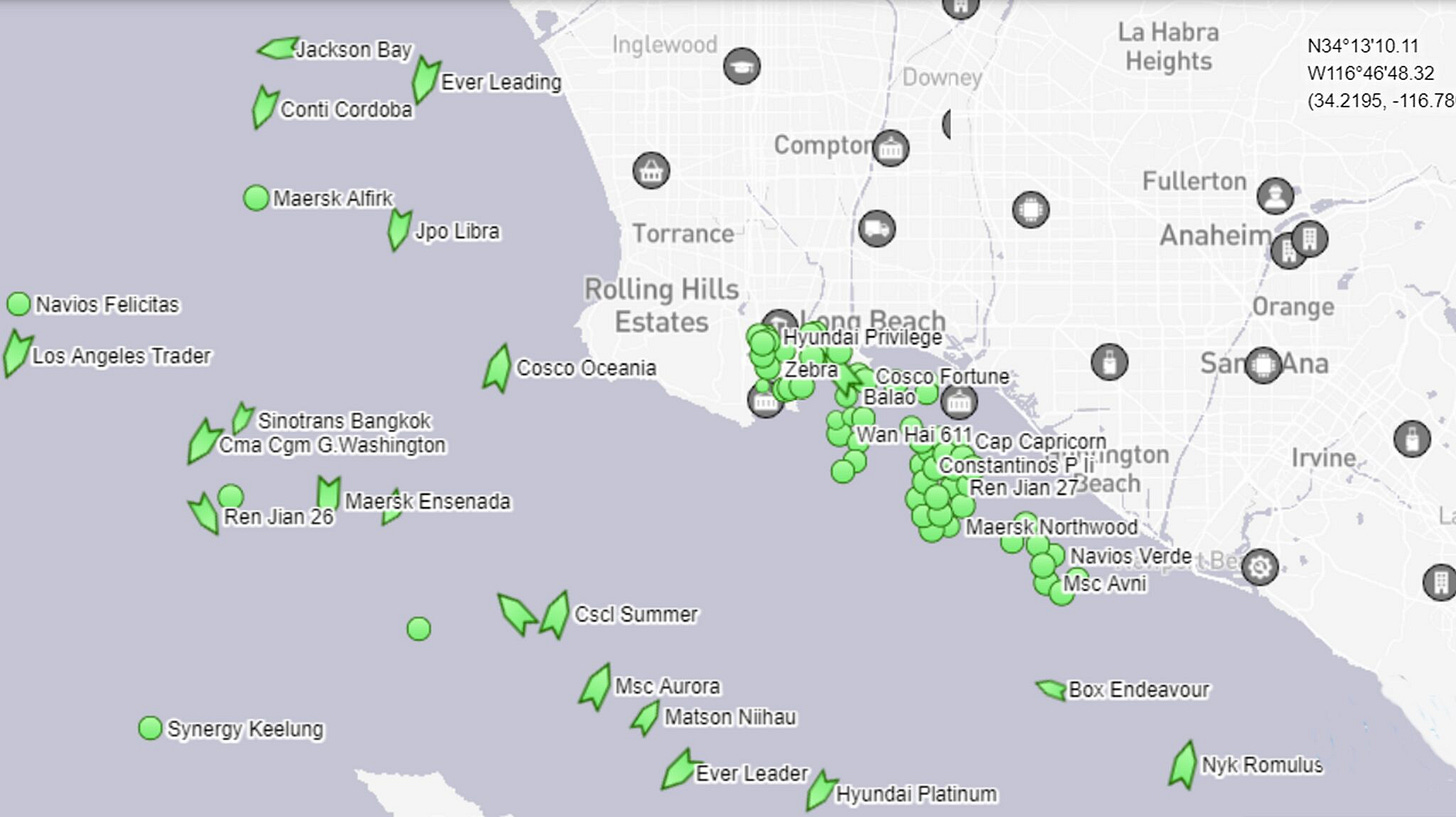

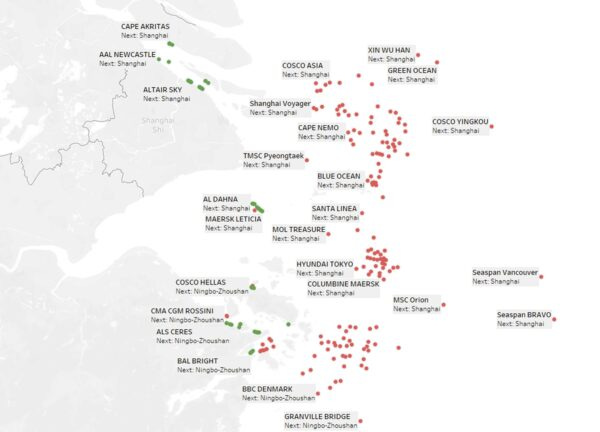

Staying on the maritime theme, the global shipping disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic have resulted in gigantic container ship parking lots off the coasts of America and China. Wait times are measured in weeks. Among the largest of the concentrations, there are more than five dozen ships anchored off Los Angeles and Long Beach in America and more than 150 ships off Shanghai and Ningbo in China.4

Follow Andrew Singer on Social Media: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter.

Rupert Gethin, The Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford UP, 1998, Chapter 3.

Kurt Behrendt, How To Read Buddhist Art, The Met, Yale UP, 2019, Page 42.