This issue I look back to the past at old maps of the world. I have always loved studying and soaking in such maps, glimpsing the world as it was known, seen, and felt throughout the ages. In Chinese Art, there are profiles of two jade pieces at the San Diego Museum of Art that are a pleasure to behold.

Ancient Maps of the World

“When did ancient mapmakers stop orienting maps with south at top and who was responsible for the change?”

I was asked this question after a talk I gave recently to the Asian Arts Council of the San Diego Museum of Art on maritime trade routes between Europe and Asia during the eleventh to eighteenth centuries. The twelfth century map pictured above generated the question. The great Arab geographer, al Sharif al-Idrisi, prepared this world map on which he placed south at the top. The three dots at upper right of the al-Idrisi Map are the source of the Nile River connected to a mountain. Asia is off the left, and an upside-down Europe is at the bottom right of the map.

There was originally no accepted tradition or standardization for how to orient maps in the ancient world. Various cultures used different representations to reflect their own world views. Even within cultures, though, there were examples of maps with south, north, and east orientations, i.e., at the top. West was apparently disfavored across cultures because it was the direction of the setting sun.

Islamic mapmakers often placed south at the top of their maps like al-Idrisi, but not always. One theory is that since most early Muslim cultures were located north of the holy lands of Mecca and Medina, maps were oriented so that the viewer looked up towards these holy lands (in such case, to the south of where they lived). Another thought for this orientation is that since the Nile River flowed northward, maps were oriented with the source of the Nile (which was to the south) at the top.

Ancient Egyptian maps were often oriented with east at the top because it was the position of sunrise. Medieval European maps, including this 1321 mappa mundi by Pietro Vesconte, were also often oriented with east at the top, thereby placing the center of the Christian holy land from Europe at the top.

However, some European maps also referenced south at the top. A theory for this southward orientation of ancient European maps is that it aligned with the philosophy of Aristotle. Aristotle felt that the heavens had an up and down, that motion originates and moves to the right. Thus, when looking up to the south on a map, the movement was to the right toward the "nobler and superior direction." This Aristotelian philosophy was also apparently favored by the early Islamic world.

Interestingly, Chinese maps were often oriented with north at the top, even though Chinese compasses pointed south and the north was considered dark and foreboding. Such is the case with this late fourteenth century map entitled, “Da Ming Hunyi Tu,” a “Composite Map of the Great Ming Empire.” A theory for this counterintuitive orientation is that it meant that the Chinese people looked up (to the top) toward their emperor who lived in the north. North was thus a sacred direction.

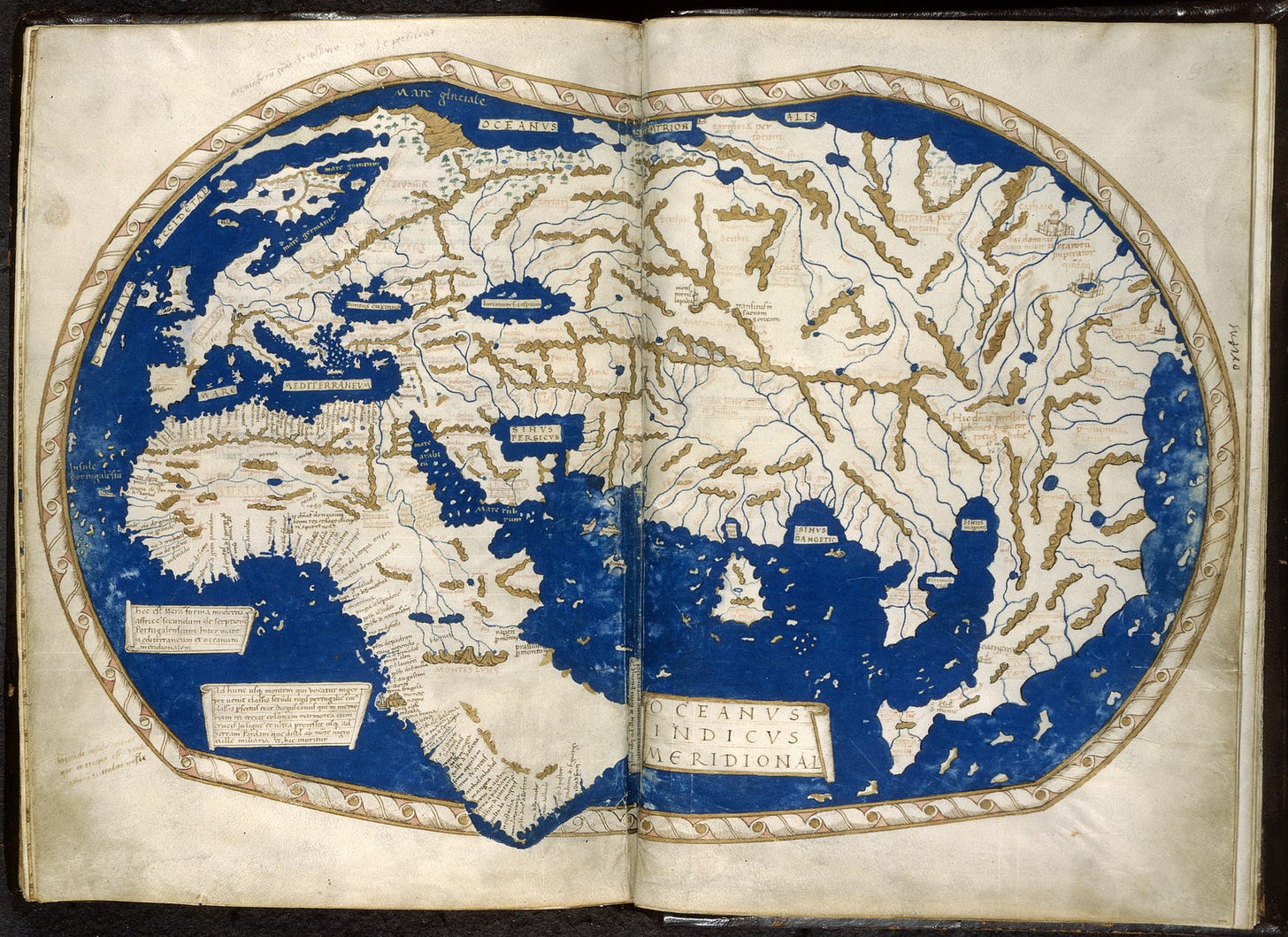

Maps began to become more standardized throughout the world with north at the top in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries when the Europeans began exploring the world in more earnest and became dominant. This was in significant part based on translations of Ptolemy’s, newly-rediscovered 2nd Century AD Geography as it became the model for most maps thereafter.

The 1489 Martellus map of the world reflects this, while also showing the water connection around the southern tip of Africa that Ptolemy did not. The mid sixteenth century Mercator Map also held the same orientation. By that time as well, advances in navigation meant that the Europeans were sailing the world based on the fixed North Star, and this was put at the top of the maps.

North has been at the top ever since.

Chinese Art

I recently attended a virtual docent tour of the Asian Art Collection at the San Diego Museum of Art. A two-thousand-year-old Hand Dynasty nephrite jade dog and a Ming Dynasty nephrite elephant caught my eye. As a bonus, I learned later that there is also a Qing Dynasty jade elephant in the Museum’s collection.

This recumbent dog was carved during the Han Dynasty (220 BCE – 220 CE). It is a subtle, peaceful depiction of an animal at rest. The ancient craftsman used the natural variation in the coloration of the stone to great effect.

This piece is a weight of the type used in tomb burials to hold down the edges of garments and textiles. According to the Museum description, “unlike the more iconic, heavily symbolic, linear and abstract styles of earlier periods, this figure—with its modeling and sparing use of incised lines—reveals the new, realistic style of the Han period, reflecting an increased interest in the natural world.”

More than a millennium later during the late sixteenth or seventeenth century, another Chinese craftsman carved this enchanting elephant. Though the tools available to him during the Ming Dynasty were less rudimentary than his predecessor in the Han Dynasty, the basic techniques used to abrade what is one of the hardest known stones would have been the same.

The following is the write-up on this piece from Selections from the Chinese Collection, Sung Yu, Forward by Stephen L. Brezzo, 1999:

“Dappled brown, this elephant is in a sitting posture. Its head turns sharply to the viewer, its tail curls to the front, and splendid trappings covert its body. The saddle pad is decorated with meanders, and the lower edges of the caparison are bordered with cross-hatching and draped tassels. The elephant’s trunk and back are deeply grooved. Elephants were auspicious symbols of peace, strength, and prudence, and stylized sculptures of elephants such as this were frequently produced during the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties.

“This piece is generally well carved, but the back edge of the saddle cloth is not as finely finished as the front edge, and the break between the rear legs is roughly executed. This treatment is typical of Ming artisans who paid attention to exposed surface areas but were careless with profiles, interiors, and bottoms. It is in contrast to that of Ch’ing craftsmen who demanded perfection in the finished product.”

This nephrite elephant is from the late Qing Dynasty, circa 1900. The level of detail demonstrates the artist’s dedication and skill and is much more ornate than its Ming counterpart above. The elephant’s leathery skin ripples. The faces of the attendants sparkle with individual character. The headdress and robe are lifelike. You almost expect the attendants to move away as the elephant stands in readiness to lead a royal procession.

According to the Museum, “[i]mages of ‘washing the elephant’ appear in Chinese art by the fourteenth century, but its sources and meaning are not clear. This sculpture is a typical version of the subject, which shows foreign figures as grooms in the process of washing down and attending to a contented white elephant, who is elaborately adorned with bridles, hip straps, and richly ornamented rug.”

China Resources

A friend clued me into this terrific online and publicly-available Duke University database of more than 5,000 photographs taken in China (and elsewhere) during the early twentieth century: http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/gamble/about/. The pictures in the Sidney D. Gamble Collection show scenes of ordinary (and not so ordinary) life that often took place outside of Imperial venues and more touristy locales.

In celebration of International Women’s Day earlier this month, Dao Insights profiled “Ten Chinese Women You Should Know in 2021.”

Follow Andrew Singer on Social Media: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter.